Hyoun Chan Cho, M.D.

Department of Laboratory Medicine

Molecular genetic testing refers to a comprehensive group of testing methods that directly analyze structural or functional abnormalities in nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), which carry the genetic information of living organisms, in order to diagnose disease, determine prognosis, and predict therapeutic response. This approach has overcome the limitations of traditional laboratory medicine, which relied primarily on morphological changes in cells or tissues and biochemical markers, and has become a key driving force that has shifted the paradigm of modern medicine toward precision medicine by elucidating the fundamental causes of disease at the molecular level. The history of molecular genetic testing began in the late 20th century, following the establishment of the structure of DNA and the principles of gene expression, and experienced explosive technological development particularly after the Human Genome Project (HGP) made large-scale genomic information publicly available.

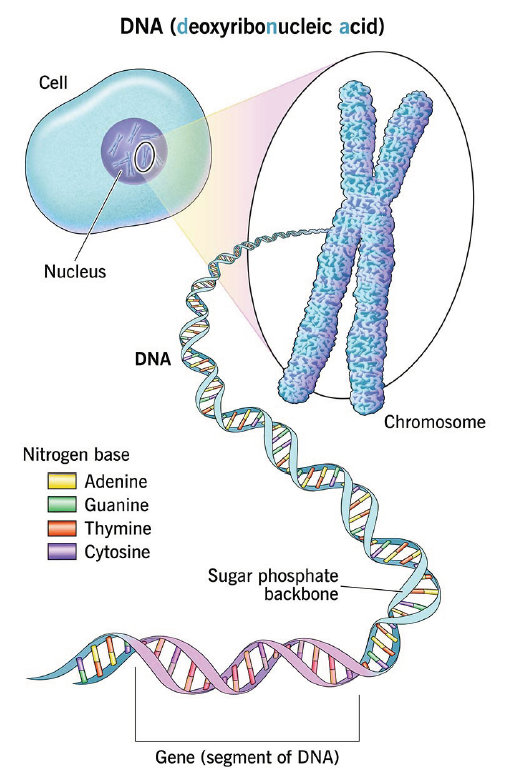

Ref) https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/dna

Fig. 1. DNA, genes and chromosomes

In the early stages, molecular genetic testing was limited to relatively simple approaches that detected only specific variants in a small number of genes; however, technological advances have progressively evolved toward high-throughput, high-resolution, and low-cost. These developments have made decisive contributions to reducing diagnostic uncertainty and enabling the establishment of personalized treatment strategies based on the genetic characteristics of individual patients across major clinical fields, including oncology, hereditary rare diseases, and infectious diseases. In particular, by providing comprehensive information on a wide range of genetic variants—such as single-nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy number variations, and structural variants—that were previously inaccessible using conventional methods, these technologies have also provided essential foundational data for research into the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis.

This review article aims to discuss in detail the revolutionary stages of development that molecular genetic testing techniques have undergone, classified by generation, and to highlight the major types of core testing methodologies currently used in clinical laboratories and their applications. Furthermore, it seeks to present the future direction of molecular diagnostic medicine by providing an in-depth discussion of the transformative prospects that rapidly converging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies will bring to the field of molecular genetic testing, along with the technical and ethical challenges that must be addressed in the future. Thus, molecular genetic testing is increasingly recognized as a core scientific technology that goes beyond a simple diagnostic tool and fundamentally transforms our understanding of human health and disease.

Developmental Stages of Molecular Genetic Testing: Technological Innovation

by Generation

Molecular genetic testing technologies can be classified into three generation based on technical principles, analytical scale, and processing speed. Each generation has overcome the limitations of the previous one and opened new possibilities in clinical and research fields.

1. 1st Generation: Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Sanger Sequencing

First generation techniques, which symbolize the emergence of molecular genetic testing, include the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing. PCR, developed by Kary Mullis in the mid-1980s, provided a revolutionary method for amplifying specific target DNA regions by millions of fold in vitro within a short period of time from extremely small amounts of DNA. This technology played a decisive role in making genetic material analysis widely accessible, and in particular, the development of real-time PCR (qPCR) enabled real-time monitoring of the amplification process and quantification of DNA, establishing it as the gold standard for infectious disease diagnostics such as viral load measurement and for gene expression analysis.

Meanwhile, Sanger sequencing, developed in 1977, was the first efficient method for determining the nucleotide sequence of DNA. It is based on the principle of chain termination using dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) and, because it can read relatively long sequences with high accuracy, it played a leading role in the early phase of the Human Genome Project. However, Sanger sequencing is fundamentally low-throughput, as it can analyze only one sample and one gene at a time, and it is limited by high cost and long processing time. These limitations, as the demand for large-scale genome analysis increased, drove the need for new technological breakthroughs and foreshadowed the emergence of second generation NGS technologies.

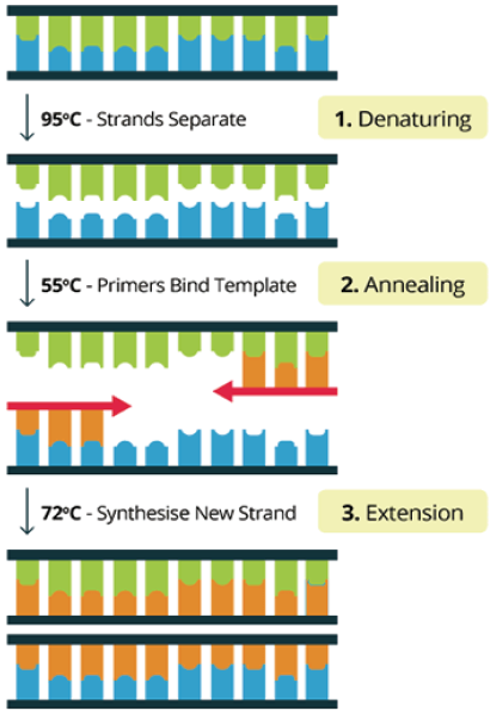

Ref) Conventional PCR Virtual Lab (http://praxilabs.com/3d-simulations)

Fig. 2. Three main steps of PCR

2. 2nd Generation: Emergence of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Next-generation sequencing (NGS), also known as massively parallel sequencing (MPS), which began to be commercialized in the mid-2000s, brought the greatest revolution in the history of molecular genetic testing. NGS adopts a method in which millions of small DNA fragments are immobilized on glass slides or beads and sequenced simultaneously in parallel. As a result, analysis costs have decreased exponentially and processing speed has dramatically increased, thereby markedly reducing the time and cost required to sequence an entire human genome.

The representative NGS technology, Illumina’s Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) method, determines DNA sequences by optically detecting fluorescent signals generated as nucleotides are incorporated one by one during DNA polymerization. Another technology is ion semiconductor sequencing, which is based on detecting electrical signals generated by changes in hydrogen ion concentration released during nucleotide incorporation. NGS enables WGS, WES, and targeted panel sequencing that analyzes only genes of specific interest, thereby successfully standardizing comprehensive and precise genetic information analysis for the diagnosis of hereditary diseases and cancer. With the advent of NGS, molecular genetic testing has advanced from analyzing a small number of genes to simultaneously analyzing thousands to tens of thousands of genes.

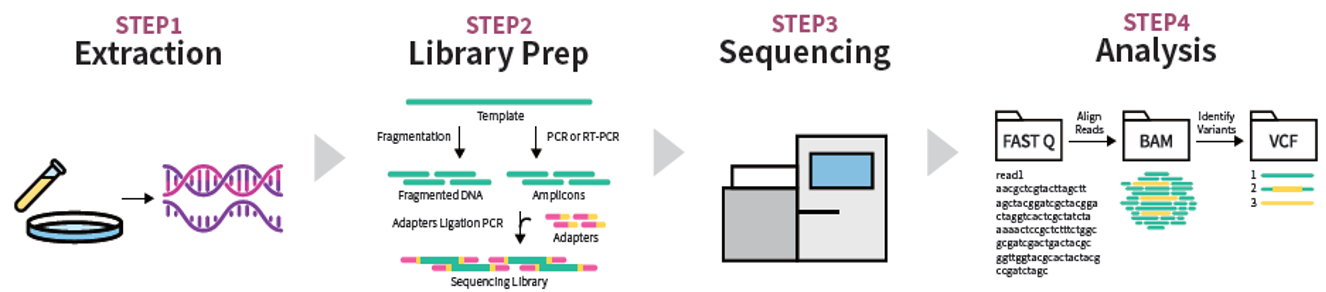

Fig. 3. NGS workflow four steps: sample extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and analysis

3. 3rd Generation: Single-Molecule Sequencing

Third generation sequencing technologies, which have emerged in clinical and research fields in recent years, are characterized by single-molecule sequencing (SMS). The core of this technology is the direct, real-time decoding of individual DNA or RNA molecules without undergoing DNA amplification (PCR). The greatest strength of third-generation sequencing is the ability to obtain ultra-long reads.

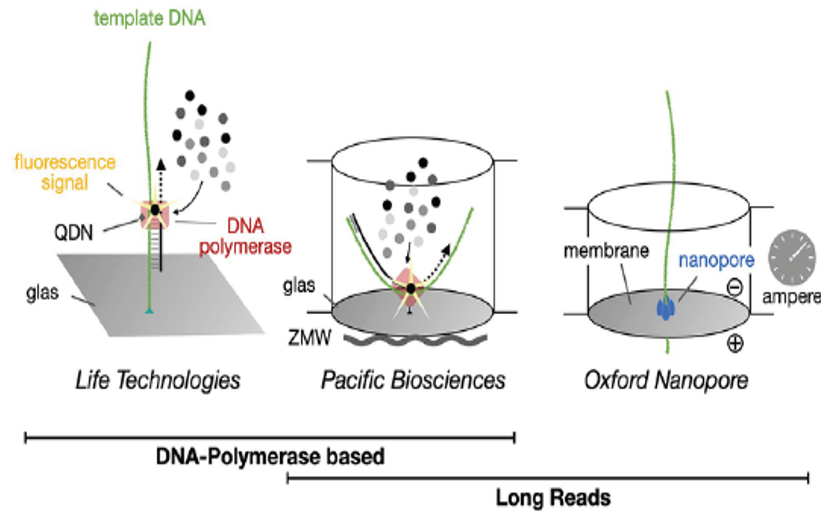

Representative technologies include Life Technologies’ Illumina sequencing, Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing, and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) nanopore sequencing.

Nanopore sequencing determines nucleotide sequences by measuring changes in electrical current generated as DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores. Long read lengths are essential for accurately analyzing repetitive regions, complex structural variation, and pseudogene regions, which have a high likelihood of false positive variant calls.

In addition, these technologies provide the potential to directly analyze epigenetic modification, such as DNA methylation, simultaneously with nucleotide sequencing, thereby further expanding the scope of genomic research. Third generation sequencing is expected to play an important role in exploring complex and subtle genetic variants that cannot be resolved by current NGS.

Ref) Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. March 2023

Fig. 4. Single-molecule real-time DNA sequencing

Types and Applications of Molecular Genetic Testing in Clinical Laboratories

Molecular genetic testing methods currently used in clinical laboratories to support patient diagnosis and treatment decisions are classified in various ways that reflect stages of technological development. In particular, PCR-based technologies and NGS-based technologies are used in a complementary manner depending on the testing purpose and the target disease.

1. Continued Use of PCR-Based Techniques

PCR, a first generation technology, still occupies an indispensable position in certain clinical settings due to its high sensitivity, rapid turnaround time, and relatively low cost. In particular, real-time PCR (qPCR) is widely used for pathogen detection and quantitative analysis in infectious diseases (e.g., hepatitis B virus and SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics), for minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, and for gene expression analysis.

Recently developed digital PCR (dPCR) provides much higher sensitivity and quantitative accuracy than qPCR by partitioning a sample into thousands to tens of thousands of micro-reaction compartments and counting the absolute number of target molecules. Such dPCR is particularly useful for detecting extremely low-abundance targets, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), in liquid biopsy applications. In addition, for genotyping, various nucleic acid amplification technique (NAAT), which are variants of PCR, are essential for analyzing the genotypes of drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP2D6) and for rapidly screening known single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants in hereditary diseases.

2. Clinical Standardization of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

NGS has firmly established itself as a clinical standard in the fields of cancer diagnostics and hereditary diseases, where large-scale genomic information is required. In particular, in cancer panel testing, NGS simultaneously analyzes tens to hundreds of cancer-related genes and serves as a key tool for supporting the selection of targeted therapies through companion diagnostics tailored to the tumor characteristics of individual patients. This provides essential information for comprehensively characterizing tumor heterogeneity, predicting resistance mechanisms, and establishing optimal treatment strategies.

In the diagnosis of hereditary rare disease, whole-exome sequencing (WES) enables the rapid identification of pathogenic variants across numerous genes in patients with complex genetic disorders that cannot be explained clinically. WES has particularly contributed to dramatically improving diagnostic yield in pediatric and neurological diseases.

Furthermore, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) is a technology that noninvasively screens for major fetal aneuploidies, such as Down syndrome, by analyzing fetal-derived cell-free DNA (cfDNA) present in maternal blood using NGS. This technology has transformed the paradigm of prenatal diagnosis by being safe for both the mother and the fetus while providing high accuracy.

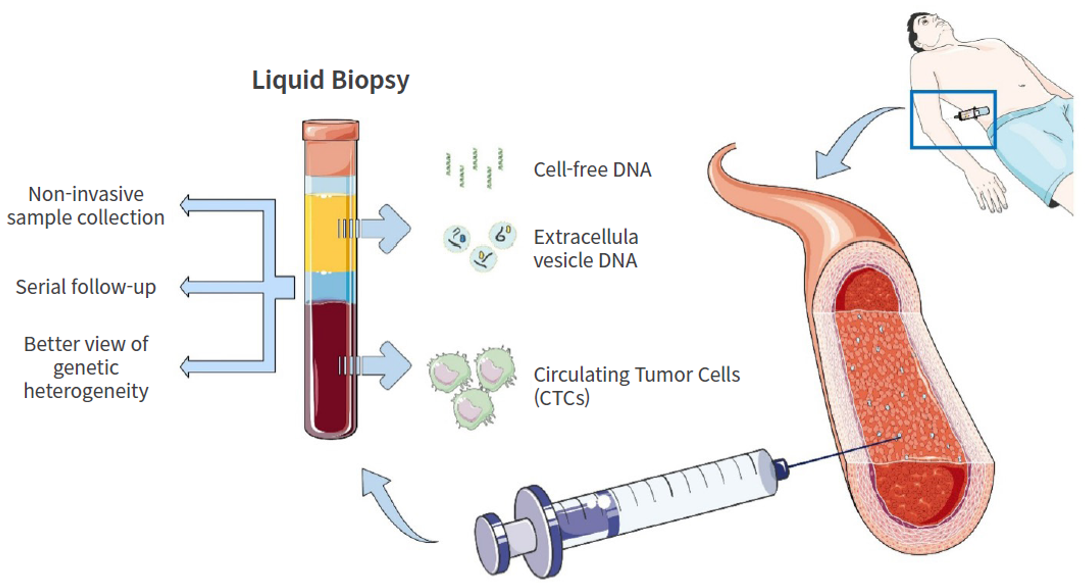

3. Development and Clinical Application of Liquid Biopsy

With improvements in the sensitivity of NGS technologies, liquid biopsy has emerged as one of the fastest-growing fields. Unlike tissue biopsy, liquid biopsy refers to the molecular genetic analysis of biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and exosome in body fluids including blood, urine, and saliva.

Liquid biopsy offers clear advantages over conventional tissue biopsy in that it is noninvasive and allows for repeated testing. It is particularly useful when tissue sampling is difficult or associated with significant procedural risk, and it has high clinical value because serial testing over time enables near–real-time monitoring of tumor genetic evolution and the acquisition of drug resistance.

Currently, liquid biopsy is actively being studied and applied in a wide range of clinical scenarios, including the detection of genetic variants for selecting targeted therapies, monitoring of treatment response, assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD), and early detection of cancer recurrence. Furthermore, this technology is expected to contribute as a transformative diagnostic platform in the future for early cancer detection in high-risk populations and for population-level screening.

Ref) Int. J. Mol. Sci.2024, 25(10), 5208;

Fig. 5. Liquid biopsy

Prospects of AI-Based Molecular Genetic Testing:

Innovation Through the Integration of Artificial Intelligence

Advances in molecular genetic testing techniques, particularly second and

third generation sequencing technologies, have ushered in the era of big data.

Even the whole-genome sequencing data from a single patient can amount to

hundreds of gigabytes (GB), and efficiently and accurately analyzing and

clinically interpreting such large-scale data has reached the limits of human

capability alone.

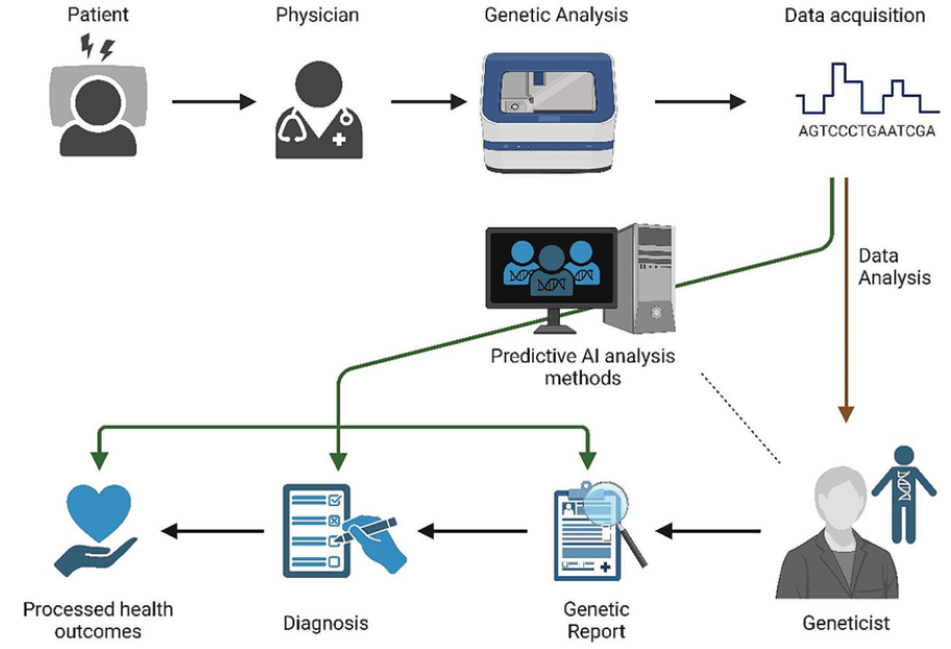

Against this background, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies are emerging as key driving forces for the next wave of innovation in the field of molecular genetic testing. Fig. 6 illustrates the workflow of diagnostic genetic testing. By using AI algorithms to compare and analyze patient genomic data, the speed of diagnosis and treatment planning can be improved.

1. Efficiency and Automation of Bioinformatic Analysis

NGS data begin as billions of short read and must undergo complex, multi-step bioinformatic analysis processes, including alignment, variant calling, and filtering. AI contributes to reducing errors in these processes and dramatically increasing analysis speed.

Specifically, deep learning models demonstrate superior performance in detecting variants in complex genomic regions (e.g., highly repetitive sequences) with much greater accuracy than conventional algorithms, and in prioritizing truly pathogenic variants from among numerous candidate variants. Machine learning algorithms automatically identify subtle disease-associated genetic patterns, gene interaction networks, and previously unrecognized diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers from large-scale cohort data, thereby improving the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tools.

2. Clinical Interpretation and Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS)

One of the most challenging steps in molecular genetic testing is identifying, among the vast number of genetic variants, the key variants that cause a patient’s disease or are associated with treatment response, and accurately interpreting their clinical significance. AI makes a substantial contribution to addressing this challenge. Specifically, in the prediction of variant pathogenicity, AI is used to quantitatively predict and classify the likelihood that a given genetic variant is disease-causing by integratively learning from extensive literature databases, functional study results, and large-scale population genomics data. This plays a decisive role in reducing the time required for clinicians to make treatment decisions and in improving the consistency of interpretation.

In addition, in the field of multiomics integrative analysis, AI integrates and analyzes diverse layers of molecular data obtained from patients, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Through such integrative analysis, it becomes possible to understand the causes and progression of disease from multiple perspectives, and by providing deep insights that reflect the functional state of disease beyond simple genetic variant information, it is expected to elevate the level of precision medicine to the next stage.

Ref) Functional & Integrative Genomics 2024:24(4)

Fig. 6. An illustration of a diagnostic genetic testing workflow

3. Future Prospects of AI-Based Molecular Genetic Testing

In the future, AI-integrated molecular genetic testing systems will become widespread. For example, approaches that combine AI-based digital pathology with NGS data to simultaneously analyze histopathological images and molecular variant information in order to maximize the accuracy of cancer diagnosis are being investigated. In addition, AI is expected to play a central role in preventive medicine by using molecular genetic testing data to predict individual disease risk and proactively recommend lifelong health management plans and personalized preventive measures. Ultimately, AI will become an essential component of clinical decision support system (CDSS) that leverage genomic data to provide individualized treatment recommendations, such as drug selection and dosage determination, optimized for each patient.

Conclusion

Over the past several decades, molecular genetic testing techniques have undergone continuous technological innovation, progressing from first generation PCR and Sanger sequencing to second generation NGS and, most recently, to third generation single-molecule sequencing. These advances have dramatically enhanced the capabilities of laboratory medicine and have played an essential role particularly in cancer diagnostics, elucidating the causes of hereditary diseases, and responding to infectious diseases. The standardization of high-throughput technologies such as NGS is already accelerating the implementation of precision medicine in clinical practice, while noninvasive technologies such as liquid biopsy are reducing patient burden and improving the efficiency of monitoring.

However, the field of molecular genetic testing still faces several important challenges. First, the quality control and standardization of the exponentially growing volume of genomic data. Ensuring data accuracy and maintaining methodological consistency are essential for clinical reliability. Second, there is a need to strengthen bioinformatic capabilities for the clinical interpretation of complex genetic variants and multi-omics data. The ability to transform massive datasets into meaningful medical knowledge will determine the success of future laboratory medicine.

Third, this involves continuous discussion and the establishment of regulatory frameworks regarding the ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI) related to personal genomic information. Protecting the privacy of genetic information and preventing the misuse of test results are important societal responsibilities that must proceed in parallel with technological advancement.

The key to addressing these challenges lies in integration with artificial intelligence (AI). AI will maximize the efficiency and accuracy of molecular genetic testing by automating complex bioinformatic analyses, integratively interpreting multi-omics data, and supporting clinical decision-making. Ultimately, through its convergence with AI, molecular genetic testing will become the foundation of an integrated healthcare system encompassing preventive management, early diagnosis, and personalized treatment, and will continue to evolve as one of the most important scientific and technological fields contributing to the improvement of human health.

References

01. Metzker, M. L. (2010). Sequencing technologies — the next generation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11(1),

31-46.

02. Goodwin, S., McPherson, J. D., & McCombie, W. R. (2016). Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(11), 333-351.

03. Meldrum, C., Doyle, M. A., & Tothill, R. W. (2011). Next-generation sequencing for cancer

diagnosis: a practical perspective. Clinical Biochemistry, 44(15), 1162-1172.

04. Tomb, R. F., Korfhage, O., & Schiroli, G. (2023). Advances and challenges in single-molecule long-read sequencing technologies. Nature Biotechnology, 41(3), 329-340.

05. Ignatiadis, M., & Dawson, S. J. (2016). Circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA for precision

medicine: the liquid biopsy road. Clinical Cancer Research, 22(19), 4791-4799.

06. Chakraborty, S., & Bhaumik, G. (2022). Artificial intelligence in molecular diagnostics: current landscape

and future prospects. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, 22(10), 875-885.

07. Green, R. C., Berg, J. S., & Grody, W. W. (2021). Clinical sequencing and the ELSI frontier. Nature Reviews

Genetics, 22(5), 299-311.